WUNRN

August 21, 2008

The U.K. and Australia Fight Breast Cancer with Free

Screening for Women 50+

By Alice Alech

- France -

Working as a breast screen radiographer or x-ray technologist can be rewarding and challenging at times but I know that detecting even a small breast cancer can make a difference in a woman’s life. That’s what makes it all worthwhile.

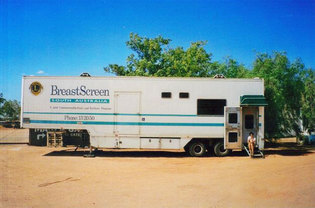

• Alice sits on the steps of

the Breast Screen unit in the Australian outback. Photograph courtesy of the

author. •

Breast

cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, with one in nine women

developing breast cancer malignancy at some stage in their lives. This is why

Australia and the United Kingdom offer breast screening free of charge,

providing programs that detect cancer at an early stage by offering mammograms

(low dose x-rays can detect small changes in breast tissue which may indicate

cancers too small to be felt by the woman or her doctor). These programs are

funded by the government for a target age group of asymptomatic women, right

through to the diagnosis. They have made a commitment to saving lives.

The National Health Service Breast

Screening Program

The development of the United Kingdom program was based on a report produced by a working group chaired by Sir Patrick Forrest in 1985. The group investigated whether it would be efficacious to set up a mass screening, utilizing mammography as the screening tool for the early detection of breast cancer. They looked at evidence from several trials conducted overseas and compared it with the number of deaths from breast cancer in the U.K.

As a result of the Forrest report, the National Health Service Breast Screening Program (NHSBSP) was started in 1988 and achieved national coverage by the mid-1990s. Today there are 84 national screening centers in the United Kingdom.

The Australian Breast Screen Program

In 1987 statistics showed that breast cancer was by far the most common cause of death from cancer in Australian women. As a result, it was decided that an organized screening program be implemented. Randomized controlled trials were conducted, research from countries such as Sweden, Finland the Netherlands and the U.K. were studied, and in 1990 The Australian Breast Screen Program was launched. Health ministers responsible for the five states and two territories of Australia jointly agreed to fund the national mammography program. Today, there are 550 locations via fixed, relocatabe or mobile screening units in the country.

Both programs target women who are well and between 50 to 69 years (the U.K. provides screening up until 70 years), the age group that has the highest incidence of breast cancer.

Screening Outreach

Contacting women in the age group is the first step in both countries. In the United Kingdom, women who have reached the age of 50 and are registered with a general practitioner receive a letter inviting them for their first screen.

In Australia women are invited to call a toll free number which connects them directly to their nearest breast screen service where they are given an appointment for their first screen.

Once on the screening list, women receive letters every two years in Australia, and every three years in the U.K., inviting them to come in for their mammograms.

Younger women have less incidences of breast cancer and so are not included in the screening programs in either country. Pre-menopausal women also have dense breasts making it more difficult to detect abnormalities on the x-rays. With age, breasts become less dense and glandular, appearing clearer on the mammogram and thus allowing the film reader to make a more accurate diagnosis. Mammograms are most effective after the age of 50, when most women go through menopause. Some breast screen units in both Australia and the U.K. will, however, accept women aged 40, especially when there is strong family history of breast cancer. These women are so appreciative of the care they receive - some have lost mothers, daughters, sisters, friends and many of them would not be able to pay for mammograms.

Each state and territory of Australia develops individually targeted messages to reach the general population. Similarly, each state does its utmost to reach the Aboriginal community through the group, Aboriginal Health Care Workers. This is not an easy task as language and cultural barriers do not make communication easy; interpreters are sometimes necessary.

Because of differing cultures among the indigenous population, outreach strategies vary from state to state; group bookings are often arranged along with transport and meals when the women have to travel great distances.

In 2005 I was part of a group that spent eight days x-raying women from the Aboriginal communities in South Australia. These women hardly ever venture out of their communities, so coming to us for screening required careful planning and coordination. They often arrived at the end of the day after traveling for hours so we greeted them with food and refreshments and tried to make them comfortable. An interpreter did most of the translating but we could easily see how relieved the women were to find an all-women team and we were thankful that most of those on our list had decided to come. It didn’t matter that they turned up six hours late.

American x-ray technologist Judy Erwin remembers her experience: “The Aboriginal women made us feel very welcome. They wanted something for themselves and often came all dressed up. There were also some stressful moments. We arrived in one remote town in West Australia, switched on the mains then discovered the entire town was without electricity,” she says.

Quality Assurance

The units where the mammograms are performed can vary in size depending on the geographic area but women can be assured of complete privacy. Every effort is made to ensure the department or mobile center is as pleasant an environment as possible. Both countries stipulate that mammographers, female radiographers or x-ray technologists specializing in breast radiography sign confidentially forms, forbidding them to disclose any information about the clients. They sometimes work in hospitals, in mobile units and often they work blind - unable to see their images when there are no facilities for processing.

Quality assurance led to the implementation of a screening protocol which stipulates that at least two readers must view screening mammograms in order to make a diagnosis. If any abnormality is discovered, the woman is called in for an assessment session and further tests. A specialized breast screen nurse is a pivotal part of the team, taking care of the woman through each step of the process. In these further examinations, the woman may need a clinical examination, more x-rays (sometimes with magnification), an ultrasound or a biopsy. The aim of the multidisciplinary team is to allay the client’s fears, or confirm a diagnosis as soon as possible and inform her of the various treatment options available.

In order to maintain the National Accreditation Standards, breast screen units are regularly reviewed by national quality assurance teams in both Australia and the United Kingdom. Each department is examined separately and accreditation is given only if the teams are satisfied that the national standards have been met.

Advances in Breast Imaging

Now that digital technology has reached the world of mammography, quite a few units in Australia and the United Kingdom have recently changed to digital equipment. The main advantage of the system is that images can be studied instantly.

Since radiographers no longer have to worry about the quality of film with the digital system, many are continuing to develop their skills in breast imaging, creating an even deeper pool of qualified professionals. Radiographers in the U.K are encouraged to continue training and can qualify to read film as well as take biopsies using imaging.

Saving Lives

A May 2008 report from The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

states that 1,614,871 women participated in the program between 2004-2005 and

that there were 3,680 cases of invasive cancer. According to Australia Breast

Screen report The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Peoples—2008, the incidence of breast cancer in indigenous

women from 2000-2004 was 84.7 per 100,000 women compared with 115 per 100,000

for non-indigenous women. Breast Screen statistics for the U.K. show that

13,443 cases of cancer were diagnosed in 2006-2007.

The World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)

concluded that mammography screening for breast cancer reduces mortality. The

IARC working group, comprised of 24 experts from 11 countries, evaluated all

the evidence and determined that there was a 35% reduction in breast cancer

among screened women ages 50-69. The need for early detection could not be any

clearer.

The British Association of Surgical Oncologists (BASO) carried out an audit of

breast cancer detected by screening between 1992 and 1996 and found that the

national survival rate at 5 years was 93% in England, Wales and Northern

Ireland. Research published in the British Medical Journal in September 2000

demonstrated that the NHSBSP in the U.K. is saving at least 300 lives per year.

That figure is set to rise to 1,250 by 2010. With time, the NHSBSP plans to

extend the age range of women eligible for breast screening to ages 47-73,

allowing 200,000 more women to be screened in the U.K.

Women who have been diagnosed and treated for breast cancer must have regular check ups by an oncologist, often having a mammogram at least once a year. Whenever time allows, I try to get a glimpse of their lives. These women explain how grateful they are that the service exists - often they did not feel the lump in their breast. They never complain about the mammogram, even though many have surgical scars making the examination painful. They see life differently.

As research continues, we may discover the cause of breast and we may be able to prevent it. However, until that time, screening offers women and the professionals who serve them a positive step in the fight against it.

.......................................................................................................................

Alice Alech is a qualified x-ray technologist and mammographer involved in the Breast Screen Program in both Australia and the U.K. She was born in Guyana, educated in the United Kingdom and has lived in the Caribbean, Australia and now in France. She travels regularly to the U.K. and Australia for work and has recently started freelance writing.

================================================================

To contact the list administrator, or to leave the list, send an email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.